'Venus Wear' Reveals 27,000-Year-Old Fashion

"Venus Wear" may sound like the latest Fifth Avenue fashion trend. In scientific parlance, however, it refers to clothing and hats that were made approximately 27,000 years ago.

Until recently, it was thought that humans wrapped simple animal skins around themselves at least 50,000 years ago, with woven clothes and textiles invented only around 8,000 B.C.

Now, an anthropologist is theorizing that clothes production was in full swing much earlier, and that sophisticated weaving techniques had already been developed by the time the Venus Wear collection made its debut.

Clues For Venus Vogue

Ninety 28,000-year-old clay fragments found in the Czech Republic in the late 1990s provided the first set of clues. Impressions show that interlaced fibers originally were pressed onto the clay surfaces. Patterns formed by these impressions hint that cord and net materials used to rest on the clay.

The woven objects themselves are highly perishable and would have biodegraded thousands of years ago. However, the intriguing clues suggested what ancient clothing and hats looked like, and how they were made.

Olga Soffer, professor of anthropology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and a former New York fashion consultant, immediately recognized the possibilities.

Hat, Not Hairdo

Recalling that she’d seen similar patterns before in France and other European countries, Soffer and her colleagues next analyzed Venus figurines, enigmatic female statuettes found throughout Russia and Europe. They date from approximately 27,000 to 22,000 B.C.

Archaeologists have known about the Venus figures for at least a century, but always thought surface impressions on the doll-like objects were just decoration. The clay impressions were said to be elaborate, prehistoric hairdos.

Not so, according to Soffer, who believes the "hairdos" really used to be woven hats, resembling snoods or upside down salad bowls, that have since worn away.

The figures weren’t just wearing hats, either.

"Our recent study of 'Venus Wear' has demonstrated that a significant number of these figurines are depicted dressed in headwear, belts, bandeaux and bracelets," explains Soffer, whose findings will be published in an upcoming issue of the journal Current Anthropology.

The impressions further suggest that the bandeaux were quite modern looking, and resembled either a strapless bikini top or a bra.

More Evidence

Soffer and her team then discovered that other objects from the same period bore impressed marks. One such object, a piece of flint from Badegoule, France, even has a burned fragment of textile fabric adhered to it.

In addition, the anthropologists identified possible weaving tools that previously were attributed to other crafts or were called "decorative art objects." Soffer instead thinks certain small needles, net spacers and forks, as well as items similar to spindle whorls and loom weights, were likely weaving and looping equipment.

Pollen at sites from Portugal to Russia, where many of the tools were excavated, also indicate weavers would have had plenty of good raw material to work with. Soffer says, "They [the pollen] include milkweed and nettle, as well as alder and yew, all of which are ethnographically used to make baskets and cordage."

Early Complex Weaving

Marijke Kerkhoven, a curator at The Museum For Textiles in Toronto, Ontario, was not surprised by the findings. Kerkhoven herself recently studied prehistoric weaving for an exhibit entitled "Mothers Of Invention: 25 Millennia Of Innovation," that will open May 31 at the textile museum.

"Twenty-seven thousand years ago, weaving appeared to have been quite complex," says Kerkhoven. "We see evidence of sophisticated weaving stripes, checks, gauze and brocade."

Weaving even may have evolved thousands of years earlier, based upon the complexity of the Venus hat and clothing impressions and the fact that these techniques already had become widespread during the Venus period.

Kerkhoven says, "The technique probably originated in the Caucasus, and gradually spread throughout Europe and other regions."

It is theorized that people from the Caucasus, a mountain range located between the Black and Caspian Seas, traveled East and West, bringing sheep and wool-crafting skills, like weaving, with them.

Early Catalogs

"Venus Wear" is still somewhat of a mystery, as researchers aren’t sure whom the Venuses depicted and what the statuettes were used for. A number of theories have been proposed.

One is that the figures may have been involved in rituals. "Facial features usually are not present on the figures, only a line sometimes exists, or impressions where a veil must have once hung," says Kerkhoven. The lack of personalization and the exaggerated sexual parts on many of the statuettes suggest they might have been deities, or held some function in fertility rituals.

Jeff Illingworth, senior analyst and conservator at the Mercyhurst Archaeological Institute in Erie, Pa., worked with Soffer on the Venus project. He says the figurines might have been "the prehistoric equivalent of the Sears and Roebuck catalogue."

He explains that craftswomen may have distributed the figurines to advertise available hats and clothing. While this idea may seem farfetched, Illingworth points out that an enormous amount of effort was spent on making textiles for the figures, but little time appears to have been devoted to making the figurines themselves. In addition to the lack of facial features, the statuettes generally have no identifiable arms or legs.

Illingworth says, "Whoever made the Venus figures wanted us to notice the intricate details on the clothing."

This Paleolithic figurine, the Venus of Brassempouy, bears evidence not of an elaborate hairstyle, but of intricate textiles in the form of a cap, say some anthropologists. The figurine is about 26,000 years old. (Steve Holland/University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

The famous Venus of Willendorf was found in Austria. (Steve Holland/University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign)

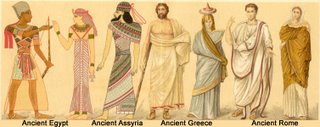

Ashurnasirpal II (left), king of Assyria, with an elaborately dressed beard, wearing sandals and a … Reproduced by courtesy of the trustees of the British Museum; photograph, John R. Freeman & Co. Ltd.

Ashurnasirpal II (left), king of Assyria, with an elaborately dressed beard, wearing sandals and a … Reproduced by courtesy of the trustees of the British Museum; photograph, John R. Freeman & Co. Ltd. Ashurnasirpal II, relief from Nimrūd; in the British Museum By courtesy of the trustees of the British Museum

Ashurnasirpal II, relief from Nimrūd; in the British Museum By courtesy of the trustees of the British Museum